Basra, meine Perle

For Zenith Magazine, I visited Basra earlier this year to write a portrait of the city - speaking to local historians, and visiting historic sites, museums & personal archives. A few photographs along with a roughly translated extract from the German below. It was a sad experience, but a pleasure to meet & work with Inam Jabori. Pick up a copy now! Via: https://magazin.zenith.me/de/g...

All images: Alannah Travers, September 2022

+++++++++++++

BASRA, Iraq -- Abandoned boats float in the distance, as sunken, rusted ships lie closer to the shore in the blazing sun. The heat hits you with full force. The corniche of the Iraqi city of Basra runs parallel to the Shatt Al-Arab, the gateway to the Persian Gulf at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates.

At least metaphorically, the scene on the coastal promenade stands for a traditional metropolis that is a shadow of its former self. Basra was once the starting point of the legendary adventures of Sinbad the Sailor, known from the tales of the Arabian Nights. The 8th-century Sufi mystic Rabia Al-Basri may be less familiar to non-natives.

Iraq's second largest city has long been home to the country's most important port. It was once the bustling city center, but was moved about 30 kilometers south to the fishing village of Umm Qasr during the First Gulf War in the 1980s. Goods traffic is still handled through its industrial deep-sea port to this day.

The metropolis is marked by the traces of the conflicts of the last decades and the consequences of climate change. Al-Ashar - the heart of the old city and a trading center for merchants from all over the world in the 18th and 19th centuries - leads to the central bazaar surrounded by crumbling buildings. Continuing towards the modern city, traditional houses, Shanasheel (known for the wooden balconies), line the old canals that are no longer used due to water shortages and pollution.

A bronze statue of poet and journalist Badr Shakir Al-Sayib, who died in 1964, gazes at empty tourist boats on the once-busy promenade. Behind the monument, a Ferris wheel marks the start of the Corniche. There is no boat traffic on the Shatt Al-Arab - the water is too shallow. Locals say they only see a passing ship once or twice a month at most.

Hadi Alawi and his twin sons occasionally take passengers on their boat. "Under Saddam we could still drink from the river," the 48-year-old says as he climbs on board. "After Turkey cut off the inflow and Iran throttled the water, the water quality also dropped downstream in Basra."

"The government was stronger – and the water supply was safer," Hadi recalls from his childhood. He blames neighboring countries to the north and east for the water crisis in southern Iraq. But Hadi believes that overfishing further up the river is also contributing to the misery. The victims are the farmers who fear for the survival of their way of life in the marshes.

Basra has been a sister city to Houston, Texas since 2015. The surrounding province of the same name has as many oil fields as the American city. 80 percent of the Iraqi government's revenue is generated in this way. The locals find that far too little arrives with them, the local people - and point in the direction of expensive new buildings, such as the »Grand Millennium«, a five-star hotel that opened in April 2022.

The air does not invite you to linger. The consequences of gas flaring as a by-product of oil production are constantly in the nose of the visitor. Despite some attempts by the Iraqi government, in partnership with energy company Total, to ramp down burning, cancer rates are rising in the area.

The situation is exacerbated by a series of other environmental crises. According to a measurement from mid-August, Basra was the hottest city in the world at 53 degrees Celsius. Nevertheless, the rural exodus is making the metropolis burst at the seams - more and more people from the increasingly uninhabitable areas in the south are looking for a living in the city. Many of the internally displaced people come from the neighboring provinces of Maysan and Dhi Qar to the north.

Current studies by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) on internally displaced persons in the context of climate change paint a clear picture and also name human factors. In Iraq, these include poor water resource management, outdated agricultural techniques, pollution, and low water flow in many rivers.

"More people mean more traffic," says Faleh Hassan in a nutshell. The 48-year-old heads the Nissan Institute for Awareness of Democracy in Basra. With regard to the data, Hassan also contradicts official government statistics, which currently count 8,000 cancer cases in the city of two million. He says, "One in a thousand in Basra has cancer," as he sips his coffee. »We are facing a health catastrophe.«

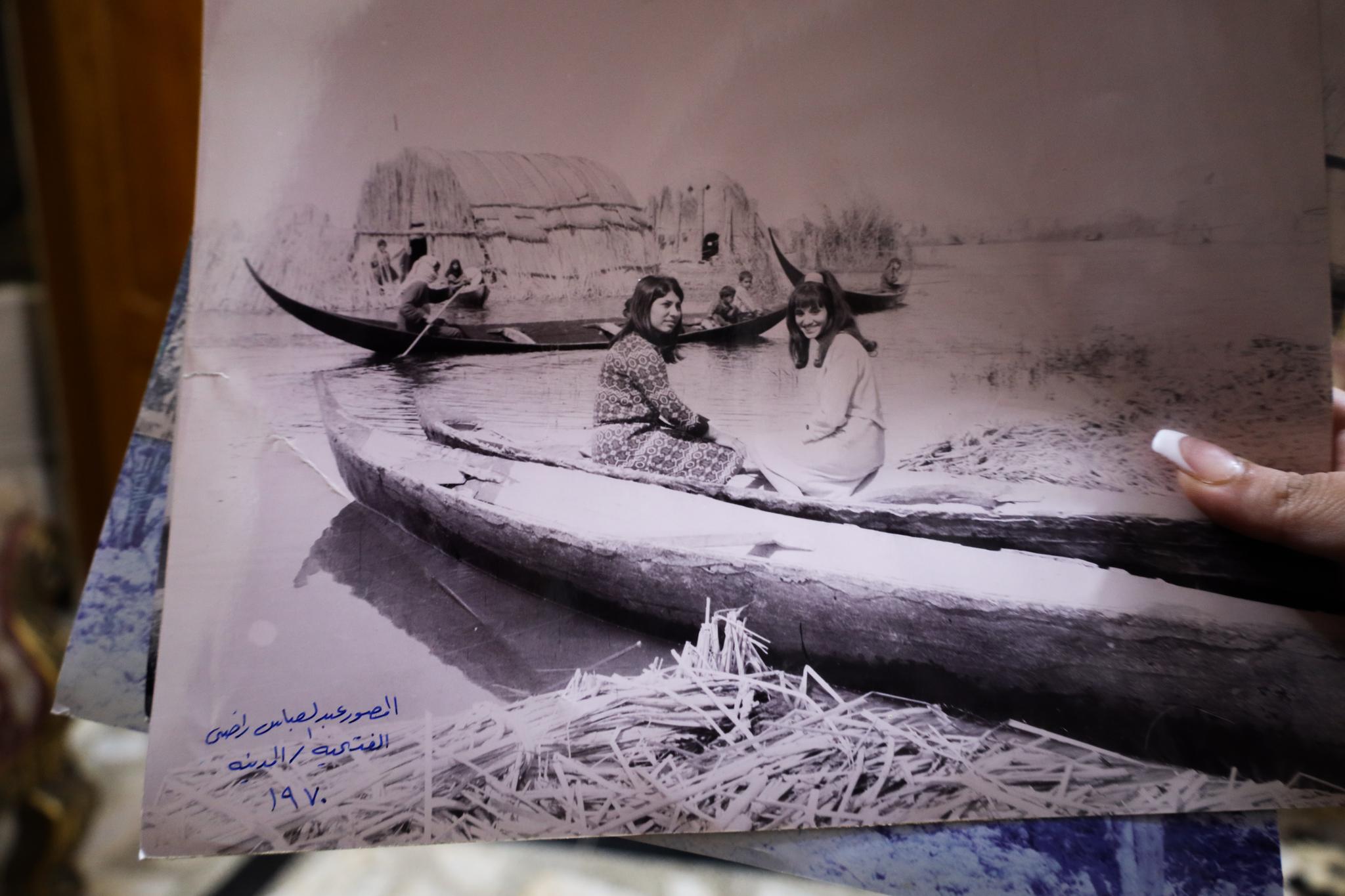

A corner away, young women are learning English. The conservative part of the population in Basra used to be less repressive, they say, pointing to their headscarves. In the 1960s and 1970s, when Hadi Alawi and Faleh Hassan were still children, Basra was considered a modern and open-minded city. From the 1980s, however, the tribes in the port city have held much more conservative views.

"I'm not allowed to do something like that so easily," says Schams, pointing to a group of young men who are looking to cool off in the water. The 22-year-old worries about the future of her city given the challenges of climate change. 'We have one month of winter and the rest of it is summer. It rains maybe once or twice a year - that's such an event that we immediately run out into the street.«

Hassan Faleh leans back in his office chair and recalls the date palms and apple trees of his youth in the Junainah district. He, too, is concerned about the future of his homeland. "Only investors, politicians and tribal members will stay," he believes. Like many other locals, he sees the war of the 1980s as the origin of the city's decline and the accompanying increase in oil production - "the main weapon of the war".

Both Gulf Wars had a devastating impact on Basra. Fierce Iranian attacks on the city's port facilities led to the decision to relocate. In 1990, just two years after the end of the war, Basra became the base from which Iraq attacked Kuwait by land, sea and air in a lightning offensive.

Nevertheless, Hassan Faleh sees the government as primarily responsible. "If they don't change their policies on pollution and climate change, there will be no life in Basra in the next twenty years," he fears.

Despite the imposing display cases that proudly display the city's rich wildlife and aquatic life, a visit to Basra's Natural History Museum is a bittersweet experience. Labid Abdullah has only been working as a museum director for a week. The 50-year-old talks to one of his employees over tea. Ali Mezher heads the museum's scientific service, which is responsible for taking soil and water samples on site and observing the region's sometimes endemic species of fish, turtles and pigeons.

"The decline in water resources here has led to the extinction of various animal species," says the 39-year-old biologist. "Our marshes are fed by the Euphrates and Tigris," he adds, describing the consequences of the decline in water. "The fish are dying, the people are moving away."

Abdullah and Mezher criticize the pollution caused by the oil industry and the threat it poses to local wildlife. "Oil and gas are needed for financing," admits museum director Abdullah, repeating the politicians' main argument about concerns in the South. »But the development of new oil fields should be stopped - it destroys our soil.«

A short walk down the river is Basra's majestic Museum of Civilization in a palace once built for dictator Saddam Hussein. Artefacts from the Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian and Islamic periods are displayed here in spectacular lighting.

Some exhibits are around 8,000 years old. The museum opened in 2016 and has been open to the general public since 2019 - but only sparsely visited. Outside, a replica winged bull, a lamassu, guards the front doors - a gift from the Italian government.

Inside, the museum conveys a picture of Basra as an early center of learning in the fields of education, poetry and music, but also glassmaking, pottery and date cultivation. In a series of dimly lit rooms, Islamic-era coins gleam in display cases, pots, pans and jewellery from Babylon, and even marriage contracts dating back to 2,000 BC.

The walk along the cultural heritage in the neighboring museum fills Labid Abdullah with pride - but also with melancholy: »We only have one history, but no future«.

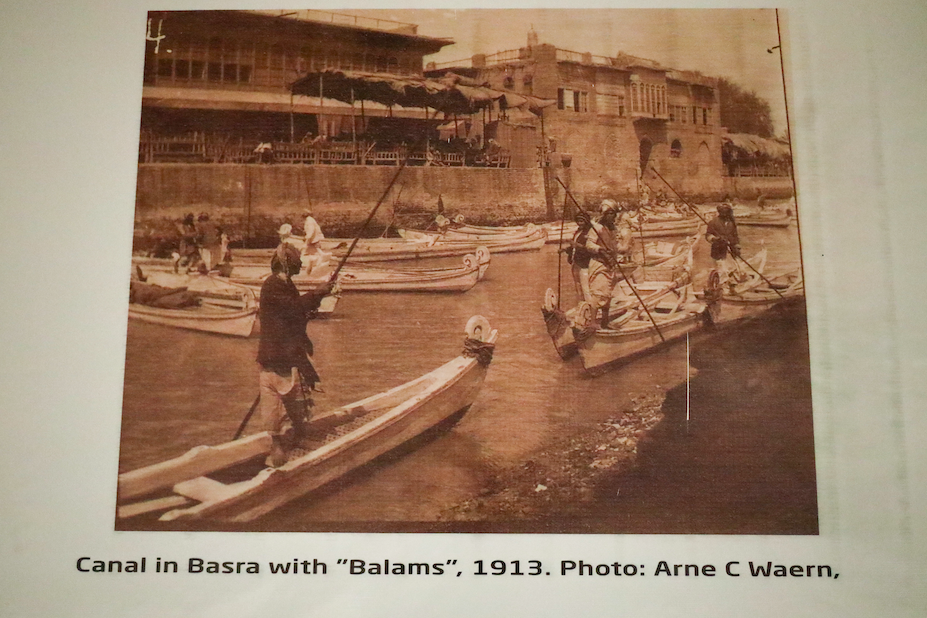

Basra was the first city founded within the Islamic Empire in AD 638 and flourished under the Abbasid Caliphs (750-1256). Records describe gardens crisscrossed by canals of crystal clear water along the length of the city - complex networks that earned the city the nickname "Venice of the Middle East" well into the 20th century.

When the Mongols reduced Baghdad to rubble in 1258, trade in Basra also suffered a slump. After the port city was conquered in 1546 and later as part of the Ottoman Empire (from 1668), new life was breathed into Basra, and international trade also picked up speed again. After the signing of the peace treaty between the Ottomans and Safavids in 1639, English and Dutch trading companies made frequent stops in the city on their journeys across the Indian Ocean. British expeditionary forces captured Basra in 1914 as part of the campaign against the Ottomans in World War I.

The British began construction of the Basra-Baghdad railway line in 1919 - the line is still in operation today, albeit with a restricted timetable. Nevertheless, the night train remains the best option on the way from the capital to the port metropolis. The British mandated power also had Basra expanded to become the most strategically important port on the Gulf for international shipping. During World War II, it was vital for transporting equipment and supplies for the Soviet Union.

The imposing ruins of the former British consulate, built in 1903, a few hundred meters from the Corniche, are now filled with rubble and plastic bags full of rubbish. In 2003, British soldiers returned to the city to support the US-led invasion.

The British combat mission in southern Iraq did not officially end until 2009. The new diplomatic mission is housed in an unadorned corrugated iron building with barbed wire near the airport. Most locals remember this period with little nostalgia, when militias also roamed the city's streets.

Hamid al-Thalimy lives on the outskirts of the city. The 54-year-old linguist is the author of 45 books, including seven on the history and development of Basra - the city is considered one of the centers of classical Arabic grammar scholars. Thalimy was born in the city in the 1960s and teaches history and language at the University of Basra.

Just as passionately as museum director Labid Abdullah, the researcher can report on the thousand-year history of his hometown. Two of his books focus solely on descriptions of Basra through the eyes of foreign visitors over the last 500 years, beginning in the early 16th century.

The size of the volumes is also a reminder of how many travelers have explored the city in the past, including merchants, doctors, Christian missionaries, but also spies from countries such as Italy, France, Great Britain, Spain and Denmark. Today, such an inventory would also have to name oil managers and journalists.

After the port was moved to Umm Qasr, about a 40-minute drive away, Thalimy explains, not many visitors came to Basra. This also reduced the exchange with the locals - a disadvantage for both sides. In addition, the increased security restrictions resulting from the recent conflicts restricted access to the once comparatively safe and prosperous province in the south. »City life was less busy – also at the expense of cultural exchange.«

Thalimy remains diplomatic when asked how else the city has changed in recent years. Nonetheless, it is obvious that he regrets the neglect and decline of the education system. "Many good teachers have left Iraq," he says. Since 2003 it has not been possible to close this gap again.

Basra has changed dramatically in recent decades: socially, politically and ecologically. Today, the area is dominated by Shiite militias, such as Muqtada al-Sadr's »Saraya Al-Salam«, who are competing for power with the pro-Iranian Popular Mobilization Forces. The port and thus the connection to the rest of the world is largely idle.

When asked about the future, the historian blinks. He would move abroad if it weren't for his library. He believes Basra will develop into an oil town. A city where you can work but not live. He pulls out a box of black-and-white photographs, flips through the 1950s shots of the city, and bows his head. No doubt modern books would continue to be written about the city's magnificent, rich heritage. "There was once a city called Basra... that's how they would begin."