Sharya Camp, Kurdistan

Iraq’s forgotten IDPs

In Sharya, under the hot August sun of northern Iraq, around 18,000 displaced Yazidis shelter in 4,000 tents. An estimate of the layout of the camp suggests that it is home to approximately 3,000 families, and the stench of rubbish hits you well before you can make out the endless lines of tatty fabric structures. It is a devastating place.

Established in 2015 and run by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), with funding from the Turkish emergency AFAD, Sharya Camp is a home to the ‘Internally Displaced’ (IDPs). Its inhabitants are drawn from the Sinjar region of Iraq, where they fled Islamic State’s ethno-religious genocidal campaign in 2014. Seven years to the month I first arrived in Sharya, IS militants had just begun their reign of terror across Sinjar, displacing an estimated 450,000 Yazidis, not including those who were killed or kidnapped. It was a grim anniversary, and one that passed with little international commemoration, nor any sign of a long-term agreement or resettlement plan. On August 3, 2014, Yazidis fled from their villages and towns; in 2021, Sharya is just one IDP camp that thousands call home.

I hadn’t been entirely sure of my decision to join some friends and their NGO until I landed in Erbil, but I was intrigued to see the area and convinced myself that it would be a worthwhile trip even if, ultimately, there is no such thing as a selfless task. I was embarrassingly unprepared for the extreme conditions and poverty. Temperatures of 40C and lack of air conditioning inevitably exposed poor sanitation; pits of plastic and polluted streams surrounding the camp prompted not just visual reminders, but the sense of utter despair. People live in the camps because they are unable or unwilling to return to Sinjar province, with its landmines, mass graves, and memories. They stay, and it is awful.

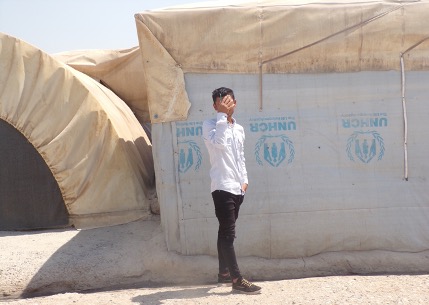

Entrance to Sharya (also Sharia). Credit: Alannah Travers

A few days before leaving, I read two recent papers by the British academic, Gina Vale: “Case Note – Justice Served?: Ashwaq Haji Hamid Talo’s Confrontation and Conviction of Her Islamic State Captor” (Journal of Human Trafficking, Enslavement and Conflict-Related Sexual Violence, 2020), and “Liberated, not free: Yazidi women after Islamic State captivity” (Small Wars & Insurgencies, 2020). Gina also kindly directed me to Foster and Minwall’s research article, “Voices of Yazidi Women: Perceptions of journalistic practices in the reporting on ISIS sexual violence” (Women Women's Studies International Forum, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2018.01.007), which I was glad to have read on the flight.

The grotesque acts of sexual and physical violence that Yazidi women and young girls have suffered at the hands of IS are well known, with unbearable experiences which I will not go into. For those who can bear, Dunya Mikhail covers the brutality in her book, The Beekeeper of Sinjar, poetically telling the stories of women and children – and men – who survived IS captivity, smuggled out by Abdullah Shrem (referred to in Christina Lamb’s Our Bodies). Shrem lives in Dohuk, the city I watched sparkling in the distance from our rooftop. I could only manage a few pages at a time.

In their article on the harmful practices of journalists who interviewed Yazidi survivors after their liberation with very little tangible gain, Foster and Minwall warned against the false hopes and expectations that were played upon to secure testimonies. I did not set off with the intention of writing about any specific experience (or even, initially, at all), but the article offered an important guide for interacting with the women I was to meet; avoiding certain language and asking probing questions, for example, and accepting how little I would ever know about their ordeal, nor be qualified to put into words.

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

I encountered brave and inspiring, fiercely intelligent young men, too, during my time at Sharya and the nearby Kabartu Camp, where I spent afternoons teaching English (and learning Kurdish) at the community centre. The dynamics of the men and boys are evidently complex; many expressed frustration at their situation, and almost every person I spoke to brought up the shortage of employment opportunities. There is also an unspoken sensitivity towards the older Yazidi boys, many of whom were trained by IS against their will. Objectively, there were fewer men in the camps I spent time in, but there was a desire among them to share their experiences and stories. Again, they are not for me to tell.

Due to Covid-19, Kabartu Camp’s only school has been closed for over a year (hence the increased role of ad-hoc lessons). I was keen to understand why it had not re-opened. To my horror, the children guessed that it might not return until November or December. My students were smart and curious and desperate to study. One particularly extraordinary and thoughtful boy asked for my (worn) book on coping with anxiety. Along with the rest of his class, he is full of dreams for the future. Mostly, these take the shape of reaching Europe.

It was unsurprising to learn that the majority of young people are keen to leave. There is a deep and embedded sense of betrayal among the Yazidi community against Iraq, with many telling me how they felt that Iraq had completely given up on them, and almost all identifying as Yazidi above Kurdish or Iraqi, if at all. In 2014, as IS approached Sinjar, the Peshmerga forces fled; in 2021, there is still no plan within Iraq to close the IDP camps (nearby Syrian refugee camps, in contrast, have a timeline for closure).

The Yazidis may be a self-contained and independent community, but it is an international outrage that so many feel – with no lack of evidence – that no one cares about them. The lives of Yazidis in camps across Iraq cannot be left to NGOs, however noble their intentions, and there is an evident sense of frustration directed at the volunteer organisations which regularly come and go, leaving little changed and failing to offer any long-term solutions.

This is also not an irrational feeling, and the absence of larger NGOs across these IDP camps – Save The Children, War Child, Oxfam – is striking. Perhaps it is obvious that funding tends to follow the security risks posed by potentially previously radicalised Sunni families, but it is nonetheless galling to see in reality. Kabartu Camp is split into two distinct sections – Kabartu I and II – with the former comprising of Syrian refugees, and the latter housing Yazidi IDPs. On the initial drive into the centre, I was struck at their differing layouts and provisions; a few days into my time there, I understood.

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

An early conversation with a German-speaking Kurd, previously based in Cologne and now Dohuk, was particularly illuminating. He explained how the IDP camps are full of corruption, with much higher funding from – and therefore lost – within Iraq. He hated the existence of these camps on his doorstep and, along with the rest of the local Kurdish community, pitied those who lived there, wishing that there were greater career prospects for Yazidi men. We spoke about resettlement, sharing the view that there should be more routes for those who would choose to leave. He was not as naïve as me in expecting them to arise soon.

Another gentleman, a Jewish-Kurd living just outside the northern village of Amedi, told me how he also felt for the Yazidis, but was more grateful for European efforts. Over chai and figs, his English-speaking daughter translated. He agreed that the camps are unsustainable, and part of the reason he rents out his second property and portion of farmland to a displaced Yazidi family. As we became better acquainted, he drew several interesting and introspective comparisons to the provision of international assistance following the invasion of Kuwait (where he served as a young Iraqi officer), and previous acts of terror against the Kurdish people, especially Saddam Hussein’s Anfal campaign. This time, his logic suggested, the West has finally done enough for the Yazidi community.

I disagree. The lack of sustained international support should shame us all. To date, the UK has not taken a single Yazidi refugee, and the fraction of military spending it would require to provide safer, more humane housing and amenities is laughable. The issue of what happens to the survivors of IS deserves a better answer, if we are to avoid the ghettoisation of another displaced community. The camps reminded me of Jaffa Camp, in the West Bank since the mid 20th Century, and the Afghan refugees of the Taliban’s previous conquest, welcoming the latest as they cross into Pakistan. The cycle of abandonment could be ended.

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Indeed, it has been a cruel irony to see IS mock the Taliban for their ‘victory’ in taking Kabul – and the country – in recent weeks. The consequences of military withdrawal are being painfully felt in Afghanistan, as the increasing numbers of asylum seekers and internally displaced scream louder. I was curious about what the implications of the Taliban’s success might mean to the camp community, and whether – despite the opposition among the jihadi world – an increased awareness of their gains, and IS terror attacks, might permeate through the tents, causing alarm or comparison. The reality was that, at least among those I spoke to, the international focus was dimmer; people cared more about their families and personal situations. My 24/7 news outlook was a luxury. The only connection was the realisation that displacement and resettlement demands are set to increase.

There are 82 million forcibly displaced people across the globe. Over two million Afghans are already registered as refugees, not including the internally displaced, and the UN estimates that over half a million more will have fled Afghanistan by the end of 2021. If we are to continue leaving countries before they are restored to pre-invasion stability, it is not unreasonable to provide safe and legal routes out.

I was, therefore, interested in the resentment towards the German Baden-Württemberg “Special Programme” scheme: the German state which relocated 1,100 Yazidi women and girls for rehabilitation in 2015. Quite aside from the jarring nature of the name, I was told, there is considerable bitterness towards these thousand Yazidis as so many more were impacted by IS crimes, many of whom have now been in IDP camps for almost six years.

For those faced with the choice, leaving the country is the preferable option. On the whole, the people I met in Sharya and Kabartu don’t have a say. Least of all the children.

Kabartu Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

If not physical rehabilitation, then, is there another way to secure meaningful justice? Inevitably, there are immense challenges facing Yazidis seeking to achieve justice through Iraqi or international legal apparatus, but it is an avenue that some are pursuing – and their treatment certainly warrants the effort. Figures such as Amal Clooney and Nadia Murad, the well-known and much lauded activist, spring to mind. There is agency – among Yazidi women, especially – to attempt legal justice, but the opportunities available to the women in the camps are, predictably, depressingly limited. I poured over Gina’s article.

Over recent years, many women have engaged with the media, lawyers, and aid agencies, yet Iraq’s courts, police force and prosecutors are over-burdened with competing (and often, imminently threatening) demands. At one stage, the Iraqi government announced that they would be willing to convict IS perpetrators in return for the one billion dollars it was estimated to cost; unsurprisingly, this international funding was not received.

Nevertheless, the successful Iraqi conviction of IS war crimes against humanity and genocide against the Yazidis marked a ground-breaking step towards justice; in March 2020, in Baghdad, Ashwaq Haji Hamid Talo (a 20-year-old Yazidi woman) played a key role in convicting her attacker. This was the first case against IS in defence of a Yazidi victim. As another recent prosecution of an IS fighter, including for his crimes against young Yazidi women, in Germany (July 2021) illustrates, too, there are grounds for such cases. German legal teams are leading the charge in international convictions.

In Iraq, the wider precedent of Hamid Talo’s case remains to be seen. There are significant issues concerning political will for further prosecutions, as well as competing jurisdictions and the sheer capacity for so many thousands of cases. Besides, perhaps I’m fixating on an unhelpful issue. Our Western form of justice is not easily applicable, not least to the vastly different, challenging context. In the same way that many women initially believed talking to journalists about their experiences under IS would raise awareness and bring help, long-term change is harder to come by. What use is a guilty verdict, or article in The Times, if your circumstances remain? I entirely understand why so many have accepted their situation.

Legal justice, international aid and resettlement aside, it is worth stressing that the majority of Yazidis in the camps had a decent standard of living before August 2014. They are as tired and hopeless for their future as we would be, which makes their culture of warmth and hospitality even more heart-breaking – and simultaneously life-affirming.

Kabartu Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers (taken by a budding photographer)

In an area where a trip to the local pharmacy often exceeds an hour, with several cups of coffee and an exchange of numbers, stories of families refusing to board helicopters from Mount Sinjar until others had taken their seats are completely believable. I received more invitations for chai and meals during my first few weeks there than I must have during ten months in Berlin. It was a pleasure to meet extended families, and fascinating to hear their views. The wife of a recent host has just travelled back to Sinjar to stay with her family, temporarily. I wonder whether he might join her. The issue is clearly alive.

It is also important to note that the KRG have the region under control, and their efforts are highly impressive. I couldn’t have felt safer, particularly as a woman, driving across Kurdistan – other drivers aside – and I never once worried for my personal protection. The existence of IDP camps, and their responsibility for them, are clearly on its agenda.

Kabartu Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

What do the Yazidi communities living in these camps want? It’s exceptionally complex, but action that restores personal loss and impoverishment would be a start. For those who feel resilient enough to return, Sinjar province requires substantial investment to rebuild its electricity and water supplies. I am also certain that the narrative of victimhood that has been appropriated to the Yazidi community through a combination of resignation, competing demands, negligence and corruption demands urgent rewriting. It is difficult to describe the powerlessness that the Yazidi people have over their lives; it feels like a physical ache. Living – existing – within these camps is adding insult to injury. In one of the camps, the corner-store is a car, driven by a 14-year-old; the need for better infrastructure could not be starker. The idea that the IDP camps might remain in operation for another several years is almost incomprehensible. It is also misguided, biased, and deeply unfair.

It has been a profoundly moving experience and privilege to spend a month in Kurdistan. The men, women, and children of Sharya Camp – and Kabartu Camp, and all the others – are wise and kind and generous. Every time someone put a baby or small child in my arms, I was struck by the unfairness of the chain of displacement; those aged five or below are living the consequences of a war that ended before their birth. The time for the survivors of IS to leave is long overdue. The decision of where they go next should be for them to make.

Sharya Camp (outskirts). Credit: Alannah Travers

Dohuk. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya. Credit: Alannah Travers

Zawar Mountain. Credit: Alannah Travers

Bidol Valley. Credit: Alannah Travers

Bidol Valley. Credit: Alannah Travers (assisted by a young volunteer)

Bidol Valley. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya. Credit: Alannah Travers

Kabartu Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Kabartu Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Kabartu Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Kabartu Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Kabartu Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Kabartu Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Kabartu Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers (with kind help)

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya Camp. Credit: Alannah Travers

Sharya. Credit: Alannah Travers

Recommended reading / viewing (with thanks to Avin Houro):

Revolutionary Ghosts, Kocho's Living Ghosts, Emma Beals: https://ejbeals.substack.com/p...

The Kurdish Project: https://thekurdishproject.org/...

Migrants & Refugees (Catholic Project): https://migrants-refugees.va/c...

Kurdistan 24: https://www.kurdistan24.net/en

Rudaw (English): https://www.rudaw.net/english

The Beekeeper of Sinjar by Dunya Mikhail (the true story of Abdullah Sharem); Kurdish Women's Stories Edited by Houzan Mahmoud; The Last Girl by Nadia Murad; Daughters of Smoke and Fire by Ava Hom; A Modern History of the Kurds by David McDowall - available to download for free at: https://b-ok.cc/book/12251009/...

Turtles Can Fly; Once Upon A Time in Iraq:

To the tune...