Supressing the pandemic in Palestine

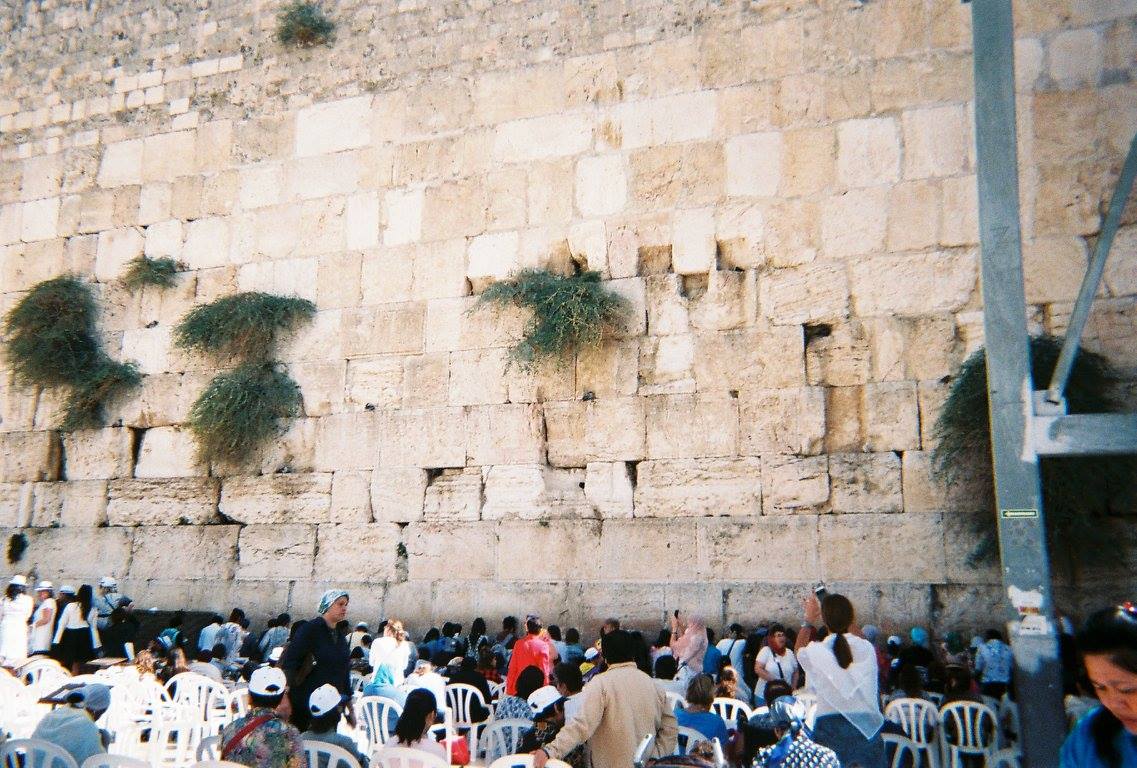

Western Wall, Jerusalem. Credit: Alannah Travers

The irony is not lost in seeking to contain the spread of covid-19 in an already contained community. But in Palestine, the infrastructure of occupation has so far proven comparatively effective in dealing with the unfolding global pandemic.

As of April 15th, 290 cases of the virus and 2 deaths had been reported; a woman in her 60s and a 55-year old man, both from Ramallah. With a population not markedly greater than its own, Israel had a death toll 70 times greater.

Indeed, the first signs of covid-19 were identified in Bethlehem on March 5th, fuelling concern that Israeli forces and religious tourists were importing the disease.

In response, President Mahmoud Abbas declared a State of Emergency and implemented a lockdown of the area, 18 days before the UK government announced lock-down measures on March 23rd, by which point 5,683 British cases (and 281 deaths) were confirmed.

Another concern had been the threat of the 150,000 Palestinian workers who commute to Israeli territory; the first victim of covid-19 contracted it from her son, a builder in Jerusalem.

On March 18th, Abbas imposed stricter measures. By the 22nd, borders were closed with the exception of movement of goods. Schools and universities were shut, and a 14-day isolation period was made compulsory.

The following day, the first case of the virus was diagnosed in Hebron.

Mahmoud Tbakhi, 17, stresses how little his life has changed since the lock-down.

Confined to his home in Hebron, he can continue his studies online and is proud that his community has responded so quickly to the crisis. Growing up in an occupied state has prepared him well for a period of quarantine.

According to Mahmoud, “Nobody dies of sickness, life is in God’s hands”. While this is a widespread – and potentially unhelpful - opinion in the Islamic region, not many Palestinians have, yet, died from the virus.

By mid-April, the Palestinian Health Ministry claimed to be conducting 1,500 tests a day, bolstered by the Chinese government’s donation of 10,000 kits. The relatively small increase of cases suggests that testing, isolation and restricted movement has helped to reduce the spread of the virus.

In such a cash-in-hand society, the financial implications of lock-down are worrying. However, as a state already heavily dependent on humanitarian aid, the need for increased international support is not inherently problematic.

Although a $5 million grant approved by the World Bank on April 2nd is a drop in the ocean of predicted economic loss, the EU has granted $77 million to mitigate the effects of covid-19 and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs has raised over $28 million.

There are anecdotal accounts of improved co-operation between the Palestinian and Israeli authorities. In Hebron’s settler community, volunteers report Israeli soldiers notifying the Palestinian side of their re-entrance for screening.

On April 5th, Prime Minister Mohammad Shtayyeh urged Israel to release 180 detained Palestinian children, protecting them from an outbreak of the virus in prisons. In a subtle challenge to those who argue the pandemic might unite the sides, this request was refused.

Ultimately, the government’s Emergency Response Plan reveals that the state has just 375 adult ICU beds and 295 ventilators, severely constraining their ability to protect the critically ill. In a population exceeding 5 million, the need to prevent the contagious disease is paramount.

Time will tell whether the Palestinian Authority’s immediate response in limiting the impact of covid-19 will slow the pace by which it spreads. If it does, the world may have much to learn from the Occupied Territories. If it does not, there will be disaster.